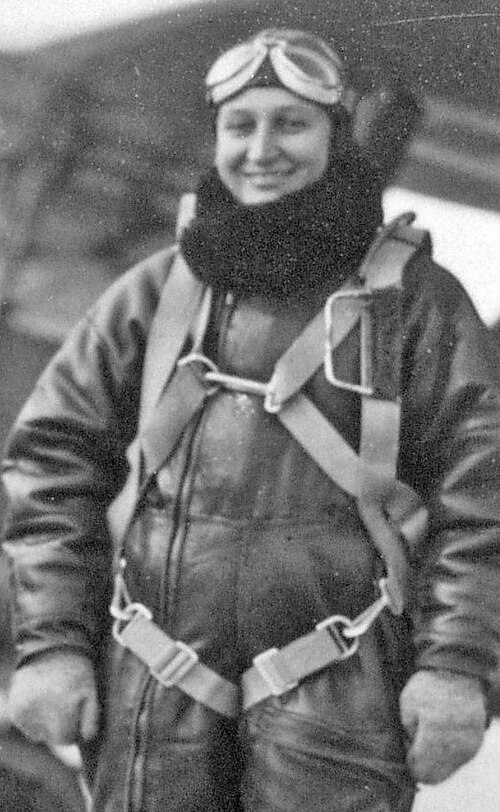

Beata Bruggeman-Sekowska

Estonia celebrates the Restoration of Independence on 20 August 1991, when the Supreme Council at 23.02 declared the illegal Soviet occupation terminated and restored the Republic of Estonia, first founded in 1918. The decision came during the failed coup in Moscow, as Soviet power weakened.

This was the culmination of a long struggle. On 30 March 1990, Estonia had already declared the 1940 Soviet occupation illegal, restored its 1938 Constitution, and reintroduced national symbols. A referendum on 3 March 1991 showed overwhelming support, with 77.8% voting for independence.

Estonian people fought for their independence from the Russian Empire, from 1917 to 1920. The most significant day was February 24th, 1918, on which Estonia declared statehood, which is commemorated as a national holiday. Independence Day is a national holiday in Estonia marking the anniversary of the Estonian Declaration of Independence in 1918.

Red terror

In the summer of 1940 the Soviet Union occupied Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as a result of the infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact signed between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on 23 August 1939. In the aftermath of the Second World War, Estonia lost approximately 17.5% of its population. Soviet Union executed series of mass deportations in Estonia in 1941 and 1945-1951. Approximately 33.000 Estonian citizens were deported. The two deportations that affected Estonia as well as Latvia and Lithuania most were executed in June 1941 and March 1949. In Estonia 14 June 1941 and 25 March 1949, are annually observed as days of mourning. The March 1949 deportation was the largest of these when over 20,000 people, mostly women and children, were deported from Estonia. People were deported to remote areas of the Soviet Union, mainly to Kazakhstan and Siberia. Entire families, including children and the elderly, were deported without trial or prior announcement. Of March 1949 deportees, over 70% of people were women and children under the age of 16.

The Baltic Way

At 19:00 on 23 August 1989, 28 years ago, approximately two million Latvians, Lithuanians and Estonians joined hands forming a human chain from Tallinn through Riga to Vilnius. The human chain they formed spanned nearly 700 kilometers, was composed of approximately 2 million people, and was a clear sign of their solidarity and wish for freedom!

Since 1940 the Baltic states were occupied by the Soviet Union which had agreed upon it previously with Nazi Germany on 23 August 1939 in Moscow and was entirely secret. This document is called the Hitler–Stalin Pact or the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact (by the surnames of the signatories: the USSR Minister for Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov and the German Minister for Foreign Affairs Joachim von Ribbentrop). Since inclusion in the USSR in 1940, the inhabitants of the Baltic states were forced to live under the dictatorship of the Communist Party where freedom of thought and speech was restricted.

The occupation continued but the USSR denied the existence of the Pact and claimed that the Baltic states had voluntarily joined the Soviet Union. On 23 August 1989, the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the inhabitants of the three Baltic states demanded public acknowledgement of the Pact’s secret protocols and the renewal of the independence of the Baltic states. The USSR acknowledged the existence of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and declared it invalid. It was one of the most important steps towards the renewal of independence in the Baltics and attracted a lot of international publicity to the joint struggle of the three countries.

Restoration of full independence remains one of Estonia’s most important national holidays, alongside 24 February, Independence Day, commemorating the original 1918 declaration of statehood.

Image: taken at a Patarei museum ©Beata Bruggeman-Sekowska

Author: Beata Bruggeman-Sękowska is an international journalist and author with a background in American Culture Studies from Warsaw University. She is the chief editor of the Central and Eastern Europe Center and president of the European Institute on Communist Oppression. Born in Warsaw and currently residing in the Netherlands, Beata has roots in Lviv, Ukraine and has Armenian heritage.